|

The castle at Newark on TrentLocation: 53N 2W (England); length 270km (170mi); drainage basin: 10,500 sq km (4100 sq mi). Tributaries include: Dane, Dove, Derwent, Erewash, Idle, Maun, Meden, Penk, Poulter, Ryton, Soar, Tame The Trent is the third longest river in England. It rises on Biddulph Moor in Staffordshire, on the western side of the Derbyshire Peak District, then flows south through the Potteries, before turning east to flow to the north of Birmingham, past Derby and Nottingham. It meets the River Ouse about 20 km east of Kingston upon Hull and from there flows in the wide Humber estuary to reach the North Sea. The Trent has been one of the most important industrial rivers in England because it passes through, or close by, so many of the early industrial areas of the country and over several historically important coalfields. It was therefore a major focus of early river traffic. However, it is not an easily navigable river and canals quickly took over from river traffic. The Trent is now one of the main providers of water for the cities near its banks. At the same time, water discharged by the many industries has, in the past, caused pollution. The big cleanup campaign on the Trent has been a major success story for river recovery.

The Trent near NottinghamNottingham occupies the northern bank of the Trent, the core of the old city sited on a high sandstone bluff overlooking the river. The city has continued to spread out north and west, with very little expansion across the floodplain of the river. The small River Leen flows in through the western suburbs, and farther to the west the River Erewash flows through Stapleford to meet the Trent at Long Eaton. The River Soar enters just down river of the confluence of the Derwent. This also doubles up as the northern link of the Grand Union canal from London. Two canals lead from Nottingham to other important industrial or port areas. One canal leads east to Grantham and the ports of the North Sea. This has been allowed to fall into disuse. The other canal - the Trent and Mersey Canal - was designed to link the Atlantic port of Liverpool with Nottingham. The short Beeston Canal leads to the heart of Nottingham and the site of its earliest industries. The Erewash canal leads beside the Erewash northward to Eastwood where it used to serve factories.

The canalside view at Nottingham.

To try to reduce the time taken to ply the Trent, several of the meanders have been cut through near to long Eaton. These include the Sawley Cut, a substantial diversion close to the confluence of the Trent with the Derwent. The Derwent meanders significantly as it leaves Derby and heads for its confluence with the Trent. Several pronounced examples of oxbows can be found in this area. An oxbow lake on the Trent can be found just to the north of where the M1 crosses the Trent. Part of it is wooded. The only development to the east of the city has been at West Bridgeford, whose name tells of the days when the river could be forded at this point and where the floodplain is exceptionally narrow. However, housing expansion only took place in the 19th century when the needs for industrial housing forced people to build on land they would previously have avoided. Before this West Bridgeford remained a tiny hamlet. Notice that the floodplain suburb of Nottingham is called Meadows, a clear indication of how the land had been used for centuries before the construction of Victorian housing. The most famous feature of the floodplain is probably Trent Bridge Cricket Ground at West Bridgeford. This is a typical use of a floodplain, flat ground that is really unsuited to housing because of the flood risk makes good recreational space with little competing pressure for the land. Opposite it is Nottingham Race Course, another land use needing large amounts of flat land. As horse race meetings are held infrequently, the race course cannot easily compete with other uses that could afford to pay more. A flood plain site which is avoided by housing development is therefore ideal for race courses. The Trent was, in the past an important industrial river. This is the reason there are so many canals meeting at Nottingham. Most of these riverside and canal side factories have now gone, but distribution depots and some factories can still be found, for example, just south of Carlton. The other site of international importance is the National Water Sports center, where a long, straight racing area has been created in the floodplain. To east and west of the city, where the floodplain is wider, the thick beds of river floodplain gravels have been extensively quarried. This has left the floodplain with large areas of unusable land. The imaginative use of this scarred landscape accounts for the National Water Sports center and for the spate of Country Parks and Nature Reserves that occur among the former gravel workings. Much of the Trent close to Nottingham is embanked to try to prevent flooding. Embankments (levees) can be found opposite Long Eaton. More can be found to the east of the city from Radcliffe on Trent. An example of an embankment designed to protect a whole settlement is at Barton in Fabis opposite Long Eaton. A fine example of the use of resources is the power plant close to Ratcliffe on Soar. Here the power plant is making use of gently undulating land clear of the flood risk associated with the floodplain, while at the same time making use of the river water for cooling the generators and relying on the local availability of Nottinghamshire coal. Yet another use of the floodplain is as the site for reservoirs. These are found just west of Long Eaton. Similarly, the city sewage works is on the floodplain close to the University, just west of the city center.

Lower TrentThe entire length of the Trent from Nottingham to its confluence with the Humber is low lying. This has naturally been a land of marshes, and close to the Humber the vast flat land used to resemble the East Anglian fens, with great swathes of reeds and rushes. Improvement over the centuries has reclaimed the land, first for meadows and then in part for cultivation. Below the surface lie important spreads of river gravels. These have been quarried with the result that large numbers of gravel pits are found along much of the river's course. The lower Trent is one of the great meandering rivers of the Midlands. Meanders are broad and oxbows are common as the river flows aimlessly over its plain. As the oxbows increase their loops, so they are more and more liable to be cut through at their narrow necks. When this finally happens they are isolated as oxbow lakes, which gradually fill in with silt during floods. Many curving shallow trenches on the Trent flood plain tell of such former meander loops. The way that some of the oxbows have been created, and the changing position of the river, can be traced in this area using the Parish boundaries. When first established, the parish boundaries used the river as a boundary. Where the river has moved, the boundaries, as shown on modern maps, diverge from the river. It flows on floodplain some 3km (2 miles) wide. A huge swathe of land is thus liable to flooding and for much of its length the river is buttressed by natural levees which have been artificially heightened and reinforced to give a measure of flood protection to those living close to the river. Tributary rivers cannot easily reach the embanked Trent and some flow almost parallel to it for many kilometres before actually being able to meet with it. In fact, as described above, Nottingham is the only large city to be sited on the lower Trent, so difficult is it to find dry land close to the river. Thus, for example, Derby developed on the Derwent, well clear of its junction with the Trent. Only rarely does the lower Trent cut into solid rocks at the edge of its floodplain. Where it does, it gives an ideal opportunity for a settlement to be founded on dry land close to the river. One such place is at Radcliffe-on-Trent, just east of Nottingham. In this region there are some good examples of cliffed edges to the floodplain where the river has swept recently to the edges of the floodplain. One example is just north of East Bridgeford. The slopes show well on the map because it is still forested, running for many miles north to the Trent Hills. Otherwise those who founded settlements have used small patches of gravel on the river terraces that flank the floodplain. In ancient times these sites were valued because they provided dry land close to water meadows where animals could be grazed. Shelford and Gunthorpe are two of the many examples. Many of the small villages close to the river have interesting shapes and in some cases you can tell something about their history. One such is Bleasby. Here the village tentatively reaches out across the floodplain its houses strung out in a line, unlike most of the nearby compact villages. When you get to the river you can see an explanation for this unusual shape. Here lies the (former) Hazelford ferry and beside it is the Inn that used to be the focus of people crossing the river at this point. In fact, two things combined: the river can be crossed by ferry, but small areas of slightly higher land provided the site for the village and the road to reach the river throughout the year. Remember back through the centuries when much of the floodplain in winter would be wet and impassable and you can see how vital picking out patches of slightly firmer ground would have been. Below Newark the patches of gravel are much less common and in consequence fewer and fewer villages are found on the floodplain. By Gainsborough the land is so flat, and the Vale of Trent so wide, that the highest points to be seen are the levees beside the river. Nearly all the roads run on the crests of the levees and even some tiny villages are strung out along the levees, clinging to them for protection in time of flood. As a result these villages are but a single street wide and very elongated. Burringham and East Butterwick near Scunthorpe are fine examples. The marshlands of the Lower Trent are known as carrs. Now reclaimed as fertile cropland, the names are still a reminder of their former marshy past. The Lower Trent flows over one of the largest coalfields in Britain. So, naturally, as it is so expensive to transport coal, large coal-burning power plants have been built in the area. So conspicuous from the M1, these power plants actually line up along the banks of the Trent in order to use its waters for cooling. In fact together the rivers use several times the entire flow of the river as cooling water. If they simply used all of this water and never returned it, the river would dry up. In fact, nearly all of it is recycled. The steam rising from the cooling towers represents the small portion (about 3%) that is not returned to the river but lost to the air.

Photostudy of the Trent at Burton on Trent

The Trent is a substantial river at Burton on Trent. The flow here is already controlled by weirs, giving a deep channel that was suited for navigation.

The most modern of the bridges over the Trent at Burton on Trent. Notice the embankments, or levees, beside the river.

A nineteenth century addition to the Trent bridges was added to make it easier for people to walk from their homes on the east bank across the floodplain of the Trent during times of flood. The bridge continues as a high level causeway until it reaches the western edge of the floodplain at Burton on Trent

The main Trent bridge at Burton on Trent

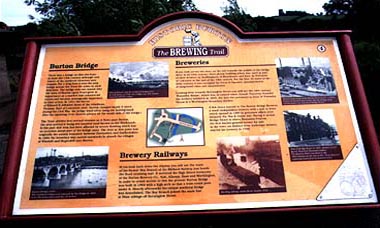

The historical focus of Burton on Trent centers on the way the brewing industry grew up close to the river, using canals as a means of transport. This information board gives details of a historical walk.

The old mills situated on an island in the river at Burton on Trent

|