|

Tributaries include: River Teith Lakes include: Loch Katrine Loch Lubnaig

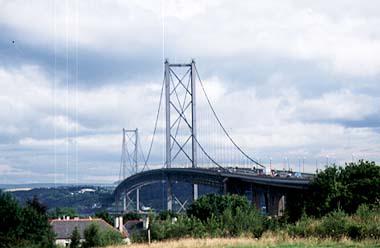

The Forth Railway bridge, one of the wonders of the 19th century engineering age, crosses the Firth of Forth at Queensferry where the Firth narrows due to hard volcanic rocks below the surface. Using the same narrow gap is the Forth road bridge, seen in the background. The picture was taken from the south bank, looking north west.

IntroductionThe eastward draining River Forth and the westward draining River Clyde dominate the drainage of the southern Grampian Highlands and the Midland Valley of Scotland. In the highlands near their headwaters, the boundary between the two river systems is clear and they are separated by some of the most famous of the Grampian mountain peaks, but in the Midland Valley, the gently undulating landscape with its smooth forms deposited during the last Ice Age, make it very hard to tell where one drainage basin starts and the other ends. Certainly a traveller from Edinburgh to Glasgow would be hard put to say when they had left the Forth basin and entered the basin of the Clyde.

The Upper ForthThere are many sources of the Forth, of which the small locks that feed the actual Forth are not the most spectacular. Much more dramatic are those of the River Teith, a long tributary of the Forth that flows into the Forth just above Stirling. Everywhere the basin of the Forth abuts against that of the Clyde. The southernmost headwaters begin on the eastern flanks of Ben Vrackie whose western slopes form the backdrop to the Clyde's Loch Lomond. Loch Ard forms another headwater, as does Loch Chon, but these are but small rock basin lakes eroded by glaciers into soft rocks during the last Ice Age. Only the northern tributary, the Teith, drains land as spectacular as that of the Clyde or its northern neighbour, the Tay. Here are magnificent Loch Katrine and Loch Vennacher, both pointing directly from east to west - the direction in which the ice that created them once flowed. Loch Katrine lies in that part of the Grampians called the Trossachs, which means bristly place, after its craggy appearance. The area is also affectionately known as the Scottish Lake District . Here the crags overlook placid lakes and forested slopes that attract many visitors. It is also the place where Sir Walter Scott set Rob Roy and The Lady of the Lake. Here, as elsewhere, hard rocks play an important part in the shape of the landscape and where especially hard gritty rocks occur they have even defied the attack of glaciers. This is why, for example, Loch Katrine narrows eastward and the valley is, in part, only wide enough for tiny Loch Achray. Loch Doine, Loch Voil and Loch Lubnaig form yet another strand to the basin of the Forth. But here the location of Loch Lubnaig is very strange because it was once the edge of the Firth basin, not a valley within it. In glacial times ice pushed from west to east over the rim of the basin and cut an enormous trench (what geographers call a glacial diffluence trough) and it is this that the loch now fills. So it was not an ancient river like its neighbours, but once a craggy ridge!

The Lower ForthThe Highland boundary fault marks the edge of the Highlands and there is a marked contrast between the Highlands and Midland Valley. The Lower Forth is almost flat, a result of a combination of deposits from the Ice Age and reworking by more recent sea waves before the land rose and left this part of the Forth as dry, if boggy, land. Here the Forth wanders without much of a gradient to direct it. The extraordinary windings of the Forth over the carselands must not, therefore, be confused with natural meanders carved by an actively eroding river with a good slope to follow. On the contrary, the Forth winds aimlessly over the same flat lands that it did when this whole area was estuary mudflats at the end of the last Ice Age. The flat land is slow to drain and so a great expanse of peat and boglands, called carse, dominate the valley of the Forth between the highland edge at Lake of Menteith and the city of Stirling. Peat cutting and the use of peat for fires used to be commonplace here in centuries past. Once a formidable barrier to travel and avoided by all, the peats were drained in the 18th century and are now fertile farmlands. The Bridge of Allen marks a bridging point for those skirting to the east of the carse and once a place where copper mines supplied metal for Stirling's Royal Mint. Here, too, are some of the early monastic sites for those who treasured isolation. Cambuskenneth Abbey is a memorial to this time. Stirling, a city of great history and importance to Scotland lies down river of the Carse and was founded at the strategic gap where the Forth cuts through the band of hard rocks that makes the Ochils and Gargunnock Hills. Here, on a craggy outcrop of volcanic rock, one of the great Scottish castles was built, dominating the landscape in the past as it still does today. Below the castle is a bridge built in the 14th century, not the first but simply the one that has survived. In the centuries before the building of this bridge battles raged for over five centuries for control of this strategic part of the Forth. Because of the natural lie of the land, most routes through Scotland run up the eastern side of the country, making Stirling the true crossroads of Scotland. The short stretch between Alloa and Kincardine sees the river meander across the fertile coastal plain. It also widens noticeably on its last stretch to the open waters of the Firth of Forth. At Kincardine the A876 marks the last of the traditional bridging points of the Forth before it widens into the Firth of Forth.

The Firth of ForthThe most obvious difference between the two great rivers of the Midland Valley is in the shape of the firths (estuaries). Whereas the Firth of Forth is straight and funnel-shaped, opening wide directly to the storms of the North Sea, the Firth of Clyde is narrow and twisting, a feature that provides shelter from the storms of the Atlantic. The Firth of Forth narrows only once as it opens out into the North Sea, and this is where hard rocks have made erosion difficult. The hard volcanic rocks lie just below the shallow waters of the Firth and provide the stepping stones on which the Forth rail and road bridges were founded between Queensferry and Rosyth.

Rivers of the LothiansThe eastern Forth is dominated by a wide estuary, the southern part of which is occupied by the Lothians. The Forth estuary is not hemmed in by mountains like the Clyde. Instead, a wide area of low lying land flanks the estuary on both shores. On the north shore lie the carselands near Stirling, but in the south is more undulating country, the Lothians. Several rivers flow across this area, the Esk and the Tyne being the largest. Farther west, the Water of Leith flows through Edinburgh and west of that again, the River Almond flows through Livingston. All flow north east, rather surprisingly as they would have much shorter paths if they flowed directly north. To understand why the rivers flow the way they do, and why the rivers are sometimes a curious fit for their valleys, we need to look back at the underlying rocks and the effects of the Ice Age. Although they might not be as noticeable elsewhere, the low lying land of the Lothians makes the isolated hills that dot the area between the Southern Uplands and the Forth stand out from the landscape very dramatically. There are many upstanding and craggy hills in the eastern Forth estuary. All have their origins as volcanoes. The most famous of all is Castle Rock on which Edinburgh Castle is built. But it is the Pentland Hills that dominate the region, separating Mid and East from West Lothian. The sides of the Pentlands are steep, as are the Lammermuirs and the Moorfoots. All these steep sides are a reminder that erosion often follows the lines made by ancient faults. All of these hills tend to run from south west to north east. Before looking at the rivers, it is important to know how the Ice Age affected these rocks. As in so much of Scotland, both lowland and upland landscapes still show the sculpting hand of the Ice Age. And it is this that has helped to give the Lothian rivers such unusual - and interesting - courses. Again, looking at the example of Castle Rock is helpful because it has a westerly craggy side and a more gently sloping and streamlined eastern side (which is the site for the Royal Mile). Many other craggy rocks in the region have similar shapes, known by geographers as crag and tail forms. What this tells us is that, during the Ice Age, ice sheets spread from the west and flowed east toward the North Sea. As they moved about they eroded the upstanding rocks, creating the crag and tail shapes. But they also carried enormous amounts of debris, and this they spread over the Lothians, then streamlined it into shapes such as drumlins which also run from west to east. So both the hard rocks and the landscape left by the ice age tend to force rivers to flow either south west to north east or west to east. But there was one more piece of sculpting to be done. As the ice melted, so vast amounts of water rushed away to the sea. But because so much sea water was locked up on land as ice, the sea level was much lower than it is today. So the huge rivers carrying the melted ice cut gorges down toward the sea. These valleys were far bigger and their slopes far steeper than those needed by the rivers of today. And so finally not only can we see the reason for their mainly north easterly and easterly courses, but we can also see the secret of the gorges.

Rivers and settlementIn most places rivers attract settlement, not just because it provides a source of drinking water but also because the loops (meanders) of many rivers give easily defended sites. But all the ancient settlement in this region is on the hills. Not just Edinburgh Castle, but on top of the other crags like Traprain Law as well. The Roman Road that forges its way towards Edinburgh also keeps clear of the Esk valley and uses the same brow of land as the A702 does today.The oldest villages, too, line the edges of the Pentlands, rather than being scattered over the lowlands. The first people to live in this area avoided the flatter lowlands in part because in the past they were marshy (hence the words muir and moss in many place names). The clay soils were heavy and hard to work with primitive implements. And an additional difficulty was that they were cloaked in the kind of oakwoods that can still be seen in the grounds of Dalkeith House. But on top of this it was also an area that was difficult to get about, in part because many of the rivers flow in gorges. The River North Esk, for example, follows a gorge for some 20 kilometres (13 miles) - such a strange feature in a lowland so close to the sea. The Upper Tyne and Biel Water similarly flow in gorges that tell of much larger rivers in the past.

River AlmondThe River Almond flows north east from just to the east of Glasgow, across the Midland valley past Bathgate, the new Town of Livingston to reach the Firth of Forth in the western outskirts of Edinburgh, just to the east of the Forth Railway Bridge.

Water of LeithThis small burn flows north east from the Pentland Hills to the west of Castle Rock in Edinburgh to Leith. Its small estuary formed the beginning of Leith harbour.

River EskThe River Esk flows north east from the Moorfoot Hills, north through Dalkeith and Musselburgh to reach the Firth of Forth just to the east of Edinburgh. The headwaters of the Esk have been dammed to create storage reservoirs for Edinburgh's water supply. Gladhouse Reservoir and Roseberry Reservoir are the largest. The North and South Esk have gorged valleys; that of the North Esk being the most spectacular. Notice that the gorges are not, where you might expect them, on the slopes of the Pentland Hills or the Moorfoot Hills, but in the lower land between them. These rivers are flowing in valleys created by the waters that once rushed away from melting ice sheets. There has not been time for the present River Esk to change this pattern significantly. The River Esk flows to the Forth at Musselburgh Curious fact: There is another River Esk - in North Yorkshire - which also has a course formed by meltwater from the edge of a glacier.

River TyneThe River Tyne has its headwaters near the village of Tynehead, southeast of Gorebridge. Starting as the Tyne Water, its steep-sided and wide channel, once created by melting waters at the last stage of the Ice Age is overlooked by Crichton Castle and Oxonford Castle. Flowing onward, the Tyne turns east to flow past Ormiston and then gathers more tributaries from the Lammermuirs such as the Birns Water at Saltoun. Then it continues to flow over deposits from the last Ice Age through Haddington and East Linton before flowing out to the sea between the spits of Tynemouth just north of Dundee.

Pictures of the Forth and its tributaries

Close to Stirling, the Forth meanders considerably over the Carse of Forth. This picture of an oxbow on the Forth was taken from the Wallace Memorial.

The bridge over the Forth at Stirling. This is one of the most important crossing points of any river in Scotland and has been the site of famous battles. The picture, taken from Stirling Castle, looks north toward the Wallace Memorial.

Close up of the Stirling Bridge.

The Forth Road Bridge at Queensferry. Both rail and road bridges are sited where hard volcanic rock is close to the surface and can make good foundations for the structures.

Many of the small rivers in the Lothians have upper gorged sections. Most still have forested slopes and these have formed the core of some countryside parks. This is the North Esk.

Musselburgh was the lowest bridging point of the Esk. The old bridge has now been bypassed by a newer structure, although the coastal route along the south of the Firth of Forth remains as important as ever. The river is dammed at this point, and the Esk through Musselburgh is no longer tidal. |