|

The Calder flows down the eastern flanks of the Pennines before finally joining the River Aire near Castleford. For the majority of its journey, the Calder cuts a broad, stepped valley into the Pennines. The stepped nature of the valley sides reflect the bands of tough and weak rock of the Pennines, with the gritstone making the risers and the soft shales forming the treads of the staircase. Most of the towns and villages were sited on the treads. Few people actually lived by the river because here the valley was especially steep-sided, locally known as a clough. The Calder is not a large river, but it has proved to be one of the most important rivers in the history of the development of the Industrial Revolution in Yorkshire, for along its banks, or those of the canals that have largely replaced it, lie many of the founding textile towns of the Yorkshire Pennines. In the earliest days, the fast flowing waters of the Calder provided a source of direct water power. The first factories that were built in the Calder Valley were powered by waterwheels and thus needed to be sited where the river flowed fastest. Places like Halifax owed their initial growth to their being in the upper (fast-flowing) reaches of the river. As time went by, and especially when canal transport and steam power became important, the only way that these early industrial towns could continue to compete with the rapidly-growing coalfield towns like Bradford was if they turned their river into a canal and began to import coal for newly-installed steam engines. This is why, for a large part of its length, the waters of the Calder form part of the Rochdale canal and the Aire and Calder Navigation. Some places on the Calder

Halifax

The River Hebble is dwarfed and ignored by the by-pass at Halifax. The river is between the mill buildings at the bottom of the valley.INTRODUCTION

Halifax is a medium sized industrial town in a steep-sided valley (or dale) on the Yorkshire side of the Pennine Hills. The population is about 192,000. The name Halifax may mean 'holy flax field', that is the place belonging to a church where flax was grown. The small River Hebble runs in the bottom of the valley. The Hebble is too small to be used by boats. The Hebble flows into the larger River Calder, but this, too, cannot be used by boats. No ancient route passes through Halifax. In winter it can be cold with snow. The soil is not very fertile and it has never been an important crop-growing region.

2. HALIFAX IN THE PAST

Halifax is crammed into the bottom of a steep-sided valley, or clough. For many centuries few people settled in the valley where Halifax now stands. There were too many things against staying there: the soil was poor, the climate was cool and wet, the land was steep, the fast-flowing river could not be used by boats and the valley was not on an ancient route. As a result, few people came past, and few lived there. Even the Saxons did not build a town at Halifax. The story of Halifax is how what started out as a place to be avoided, eventually became one of the most successful industrial towns in England. The first signs of change came after the Norman Conquest in 1066. The valley in which Halifax now stands was given to a monastery. The monks set about using the land for rearing sheep for their wool. The monks needed to have the wool woven, and for this they needed to attract people to the valley and teach them weaving skills. As a result, people in the valley began to learn weaving skills as early as the 13th century. In the following centuries more people came to the valley to make cloth, until it was dotted with smallholdings. Each smallholding contained a cottage and some land which was used to grow food. In the cottage where the family lived, they made one of two pieces of cloth each week in their spare time. There are many surviving weavers' cottages in Calderdale. Each faces south and has high upper windows - or lights - to let the light in for the hand-loom weavers. For many centuries Halifax was a very small market town. It only became larger when the skills of the weavers came into demand. It was in the 16th century that merchants started to look for places away from the traditional areas of weaving in eastern England. The valley had fast-flowing streams that could be used to wash the wool and to drive the first machines, as well as plenty of skilful people. The demand for cloth revolutionized the valley. As merchants bought as much cloth as the weavers could make, the valley became more and more wealthy. By the 15th century, there was enough surplus money to pay for the rebuilding of the churches in a grand style never before seen. This is how Halifax developed to be a thickly settled town in a land that was otherwise thinly settled, poor farmland. By the 18th century, Halifax was so wealthy that a special new trading market was built for the pieces of cloth brought for sale by the weavers. Partly covered, and on two floors, the Piece Hall, as it was named, was a splendid stone building. It still forms one of the most attractive parts of the town. However, Halifax was to become even more prosperous during the Industrial Revolution. During this time Halifax began to see great mills built in the valley bottom. The first mills used water power, but the river is too small to yield much power, so they were quickly converted to steam power, using coal brought from coal seams in the local hillsides (and brought by canal from the coalfields near Bradford). The factories began to specialize. Alongside traditional worsted cloth, Halifax began to make carpets. In time some of the factory owners became very wealthy. The best known family was the Crossleys. They patented a method of manufacturing carpets by steam-driven power-looms. This meant they could make carpets faster and at a lower cost than their rivals. In 1900, about 5000 men, women and children worked in the factory, which was, at that time, the largest carpet-making factory in the world.

What was old Halifax like? Old Halifax filled up the flat land of a bench close to the valley bottom. The old markets - the cornmarket and the food market - were right in the center of this strip of flat land. To the south of this was the famous wool market of the Piece Hall. To the north and south of the center were the mills, each with one or more tall chimneys, belching smoke. The flattest land was to the north, and here the mills spread out, using the River Hebble for water and driven by steam using local coal. The railway crammed into the town, too, forced to take a route right along the river bank. There was no room for housing in the valley bottom, so the mill houses were set in terraces up the valley sides, connected by steep, cobbled streets.

3. HALIFAX TODAY Halifax today is a mixture of the old and the new. The great mills, that were once among the biggest in the world, went silent as owners moved their machines away from the valley. Many have been knocked down, although some of the finest, including Dean Clough complex, just to the north of the center, have been completely rebuilt inside for more modern uses. In this way a few mill buildings still survive. Much of the center was built at the end of the 19th century. The carpet-makers, Crossley, paid for a town park, called the People's Park. The grand covered Borough Market is still the centerpiece of the town and inside there is still a thriving, busy market of small shops and stalls.

Traffic no longer goes through the center of the town, but uses an inner bypass road, like a city motorway. To make room for this road, great cuttings have had to be made into the hillside, while the road crosses the valley on massive concrete pillars.

Much of the older housing was built alongside, or close to, the mills where the people worked. Mill owners, like the Akroyd family, built model housing estates: The valley south of the town is narrow and gives little room for more spread-out housing. As a result the growth of Halifax has mainly been to the north of the town center.

The Dean Clough and other mills as they were before closure. Compare this picture with the picture at the top of the article.

The Piece Hall

The general setting of Halifax.

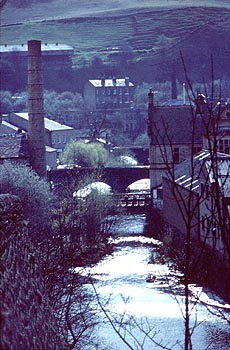

Hebden bridgeHebden Bridge is a small town on the Calder. It is one of the most dramatic examples of an early industrial town, with the mills occupying the only flat land and the houses rising up the steeply-sloping valley sides.

The Calder at Hebden Bridge, hinting at the industrial value of the river in the past and how its steep-sided valley forced mills and shops to crowd into the small amount of flat space offered by a confluence of rivers. |