|

and choose "Open image in New Window".

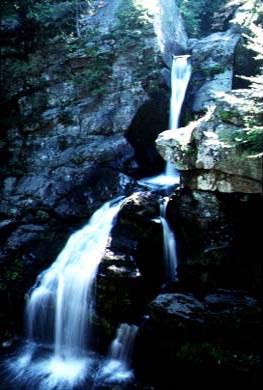

This picture shows the falls in the Kent State Park.

Housatonic River near Cornwall.

The following description is based on materials by the Housatonic Valley Association (housatonic@snet.net) / T Mitchell, Lewis Mills High SchoolOVERVIEW The Housatonic River flows 149 miles from its four sources in western Massachusetts. Following a south to southeasterly direction, the river passes through western portions of Massachusetts and Connecticut before reaching its destination at Long Island Sound at Milford Point . The Housatonic River has a total fall of 959 feet. Its major tributaries are the Williams River and the Green River in Massachusetts, the Tenmile River in New York, and the Shepaug, Pomperaug, Naugatuck and Still Rivers in Connecticut. The river's watershed, or the land area which drains into the river, encompasses 1,948 square miles and is characterized by rugged terrain giving way to rolling hills and flat stretches of marshland in the south While problems do exist in defined stretches, overall the river is characterized by high water quality. The river's flows are sufficient to support Class I, II, III and IV rapids. With over 100,000 acres of public recreation land throughout the watershed, opportunities for swimming, canoeing/kayaking, fishing, sculling, boating, hiking, camping and cross-country skiing abound. The Appalachian Trail runs along the river for five miles between Kent and Cornwall Bridge, the longest stretch of river walk between Georgia and Maine. HISTORY The Mohican family of the Algonkin Indians, who came from New York west over the Taconic mountains, were the first valley settlers. The six main tribes migrated southward as follows: the Weataugs settled in Salisbury; Weantinocks in New Milford; Paugassets in Derby; Potatucks in Shelton; Pequannocks in Bridgeport; and, Wepawaugs in Milford. The Indians named the river "usi-a-di-en-uk" which meant "beyond the mountain place". The river was sometimes known as "Potatuck", or the "Great River", until the 18th century. A large portion of the river basin was developed for agriculture in Colonial times. Water power played a prominent role in 19th century industrial development, and remnants of dams, mill races and iron ore furnaces can still be seen today. Northeast Utilities operates five hydroelectric facilities on the river today. Dams at three of these facilities - the Shepaug, Stevenson and Derby - form a chain of lakes, Candlewood Lake, Lake Lillinonah, Lake Zoar and Lake Housatonic, from New Milford south to Shelton. Much of the upper section of the river in Massachusetts is still in agricultural use, however, past industrial discharges of PCB's (polychlorinated biphenyls) into the river has created water quality problems. PCB's still remain in the river's sediments from Massachusetts to the Stevenson Dam in Connecticut. These synthetic organic chemicals can persist for decades and are a cause for concern and continued action. Further down in the valley, in the areas of New Milford and Brookfield, tobacco farms flourished until the surge of 20th century development. South of Derby, industrial development, including steel mills and heavy manufacturing, characterizes the river. This stretch is also a tidal estuary, which supports a number of critical habitats for rare plants and animals and is a significant contributor to Connecticut's shellfish population. The Housatonic estuary is the most consistent producer of seed oysters in the northeast as a public oyster bed, and generates over one-third of all oyster seed available to the state shellfish industry. RIVER PROTECTION While much of the Housatonic from New Milford north to the Massachusetts border, together with the Shepaug-Bantam tributary, qualified for protection under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, riverside communities have opted for local protection by establishing cooperative river commissions. In 1985, The Housatonic Valley Association (HVA), a non-profit watershed protection group, played a primary role in gaining permanent protection for 1,800 acres of river corridor land between Kent and Sharon through easement and acquisition by the National Park Service for the Appalachian Trail. Because of intensive residential, commercial and industrial development throughout the valley, river front protection is even more critical to ensure the continued enjoyment of this naturally beautiful river valley. Today, HVA continues its efforts to maintain the beauty and natural diversity of the river ecosystem through its Housatonic RiverBelt project. The goal of the project is to assist and support the development of local river front plans, bringing them together into a comprehensive plan with a greenway as the major component. This greenway will eventually link together existing parks, open space parcels, pathways and trails within the river corridor from its Massachusetts source to Long Island Sound. HOUSATONIC RIVER - PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION The Housatonic River begins its 149 mile journey in southwestern Massachusetts. The main stem of the river is formed by the joining together of the East and West Branches of the Housatonic River in the vicinity of Pittsfield. The East Branch begins at Muddy Pond in Hinsdale and Washington and flows a total distance of approximately 17 miles, dropping 480 feet before merging with the West Branch. Outflows from Pontoosuc Lake in Lanesboro, Onoto Lake in Pittsfield and Richmond Pond in Richmond merge to form the West Branch, which flows approximately 5 miles, dropping 140 feet before joining the East Branch. The confluence of these two branches forms the headwaters of the Housatonic River main stem, which flows in a southerly direction 132 miles to its outfall at Long Island Sound at Milford Point in Connecticut. The main stem of the river has an overall drop of 959 feet. The Housatonic River and its tributaries drain an area of 1,948 square miles. This area is referred to as the watershed. From its headwaters flowing south toward Great Barrington, the valley is narrow and the river flows quickly, characterized by several swift drops in elevation, before it emerges from the Berkshire Hills. In this section there is a good deal of commercial and industrial development. Below Great Barrington, the valley flattens and broadens out. This region is rich in farmland, and through this section the river flows more slowly, meandering its way through the valley to Falls Village in Connecticut. As the Housatonic River moves into Connecticut, the valley changes dramatically. The valley walls narrow and are flanked by hills on either side. The river now flows through a much harder substrate consisting of limestone, quartz and granite, and the river bottom becomes much rockier. There are still some agricultural activities in this northwestern part of Connecticut due to the presence of the river's nutrient rich floodplains. Just south of Bulls Bridge power plant, water is diverted from the river and pumped uphill, through a penstock, to Candlewood Lake, the first pump storage reservoir built in the country. Constructed in 1926, it is the largest (5,400 acres) lake in Connecticut. When river levels are too low to support the power generation at the Rocky River power plant in New Milford, lake water is sent rushing down the penstock and through the generators. Upon leaving New Milford, the river again changes dramatically, becoming a series of 3 in-stream lakes. Each lake is formed by a hydroelectric power dam. The Shepaug Dam forms Lake Lillinonah (1,900 acres) in Bridgewater. Farther south in Monroe, the Stevenson Dam, which is the largest, creates Lake Zoar (975 acres). The third lake is Lake Housatonic (328 acres), formed by the Derby Dam between Derby and Shelton. The flow of the Housatonic River may vary in this area. River flows are periodically "ponded" behind the dams when normal river flows are inadequate. The water is then released to turn the turbines which produce electric power. Below the Derby dam, the river begins its final change, becoming an estuary, where salt and fresh water mix. The Housatonic River estuary produces one-third of all the seed oysters which are a vital part of Connecticut's commercial shellfish industry. In this lower 12 mile section of the river are tidal wetlands and salt marshes which provide important habitat for plants, birds, shellfish, finfish and other aquatic life. The Housatonic River enters Long Island Sound at Milford Point.

The Housatonic River's major tributaries are:

HOUSATONIC RIVER - GEOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION It is believed that in its earliest formation, over 50 million years ago, the Housatonic River was a straight flowing river, originating above the Hudson Valley in New York state. The forces of erosion caused the Hudson River to eventually break through and steal the headwaters of the Housatonic, leaving it with its source as it presently is, originating in Massachusetts. The basin geology is somewhat complex, reflecting the results of hundreds of millions of years of natural events and processes. Most of the valley is underlain by metamorphic rock, mainly gneiss and schist from the Precambian era. This metamorphic bedrock was formed during the ancient collision of the North American continent with Europe and Africa some 300 to 400 million years ago. The intense pressure of the collision hardened the rock and caused it to fold and fault. These rocks form the steep mountains found in the valley. Some portions of the valley, notably north of Falls Village, south of Cornwall Bridge and near New Milford are underlain by marble and are known as the "Marble Valley". During the Paleozoic era, seas covered a large portion of the valley, leaving sedimentary rock made up of carbonate mud, shells and marine fossils, material which later formed limestone. Metamorphism turned this limestone to marble. Above the bedrock is found glacial drift, comprised of the sand, silt and boulders left spread across the land by the melting glaciers as they receded over 18,000 years ago. As the glaciers advanced and receded, the river's path was continually altered, especially through the easily eroded Marble Valley. Today the Housatonic River begins its journey in Massachusetts, separating the Taconic Mountain and New England Upland sections of the New England Physiographic Province. As it enters Connecticut's Western Uplands, it follows the Northern Marble Valley as far south as the Housatonic Highlands Plateau, two miles south of Falls Village. Here the river leaves the Marble Valley, flowing through the Housatonic Highlands until it rejoins the Northern Marble Valley at Cornwall Bridge, following it until it reaches Gaylordsville. The river then cuts a gorge through the Hudson Highlands Plateau until it reaches the Southern Marble Valley north of New Milford center. Two miles south of New Milford, the river crosses Cameron's Line and enters the Southwest Hills, flowing south easterly until it eventually reaches the Coastal Slope and discharges into Long Island Sound. HOUSATONIC RIVER - FLORA AND FAUNA The Housatonic River watershed boasts a diverse and abundant array of plant and wildlife species. Due to the changes in topography, geology, soils and climate the watershed provides the ideal setting for many types of habitat. The Housatonic River passes through five major vegetative associations: Northern Hardwoods - Found in the upper reaches of the river through Massachusetts, this region is characterized by Sugar Maple, Beech, Yellow Birch, White Pine and Hemlock. The valley of Schenob Brook in Sheffield contains unusual Carolinean vegetation, normally found much farther south along the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Transition Hardwoods (White Pine - Hemlock Zone) - Dominant species found in this area, which starts in southern Massachusetts and extends through northern Connecticut to Cornwall Bridge, are Northern Red Oak, Basswood, White Ash, and Black Birch. Some of the rarer plant species found in the region are Bog Rosemary, Marsh Willow-Herb, Canada Violet and Stiff Club-Moss. Central Hardwoods - Extending from Cornwall Bridge into New Milford, the region supports the growth of Red, White and Black Oak, Hickories, and until the blight of the 1920's, Chestnuts were predominant. Rarer plant species include New England Grape, Hairy Wood-Mint and Wiegand's Wild Rye. Appalachian Oak - Reaching from New Milford to Derby, dominant tree species include White, Red and Black Oak, Hickories, Yellow or Tulip Poplar, Black Birch, White Ash and Hemlock. Green Violet, Virginia Snakeroot, Green Milkweed, Vasey's Pondweed and Side-Oats Grama are among the characteristic rare plants found in this zone. Coastal Hardwoods - The tidal portion, or estuary, of the river flows through this zone, characterized by alder, willow, sedge, shrubs, vines, and southeastern Piedmont and Coastal Plain species. Among the rarer plant species, Eaton's Quillwort and Mudwort are found at the mouth of the river. The watershed provides a number of "critical habitats", or those which support the survival of rare and endangered species. Among the most important critical habitats are the marble ridges and ledges, caves, calcareous (calcium-rich or limy) wetlands and lakes and ponds found in the central portion of the watershed. Since the soil and surface water is less acidic, these areas are very fertile and rich in nutrients and are especially suited to agriculture. Marble ridges and ledges, such as Bartholomew's Cobble in Ashley Falls, the Great Falls area in Canaan and the Bull's Bridge area in Kent, are home to many types of uncommon ferns, including the Narrow-leaved Spleenwort and the Slender Cliffbrake. Caves, predominantly found in Salisbury, are home to bats, invertebrates and salamanders. Calcareous wetlands, such as Robbins Swamp in Canaan and Beeslick Pond and State Line Swamp in Salisbury, while supporting such lush and diverse plant species as the Spreading Globe Flower and Showy Lady's Slipper, also attract an abundance of insects and game and non-game bird species. Marl (hard water) lakes and ponds provide the ideal setting for many unique aquatic plants, such as Pondweeds, and algal and fish species. Examples found in the Housatonic region are Twin Lakes in Salisbury and Mudge Pond in Sharon.

Other habitats, and their associated species, are comprised of:

High Summits - These are wind-swept mountain summits, found on Canaan Mountain, Bear Mountain in Salisbury and Mohawk Mountain in Cornwall. Sparsely vegetated with low-growing woody and herbaceous plants, lichens and mosses, they support some species which are quite rare south of Central Vermont and New Hampshire. Black Spruce Bogs - These are poorly drained acid wetlands, characterized by a luxuriant cover of mosses, Black Spruce and Larch. Several unusual and rare species of orchids and sedges are found here. The bog areas are extremely fragile and easily destroyed. Examples are Bingham Pond in Salisbury and Spectacle Pond in Kent. Grasslands - These areas include open meadows, pastureland, grassy meadows, golf courses and hayfields. Several rare breeding birds are limited to this habitat in the Housatonic region, such as the Upland Sandpiper and the Short-Billed Marsh Wren. Coastal Salt Marshes and Mud Flats - Located in the estuary of the Housatonic River, these areas support Cord-grasses, Spikegrass, Sedges and Eelgrass. The presence of wildlife is also associated with the diverse habitat found within the river valley. Ringnecked pheasant, cottontail rabbit, red fox and woodchuck are found in Openland habitat, while white tailed deer, gray fox, gray squirrel, snowshoe hare, porcupine, ruffed grouse and woodcock are found in Woodland habitat. River edges provide habitat for primarily furbearing species, such as the beaver, muskrat, raccoon, river otter and mink. Waterfowl found in the area include the canada goose, blackduck, woodduck, blue-winged teal, ringnecked duck, common goldeneye, hooded and common merganser, peregrine falcon, bald eagle, and osprey. HOUSATONIC RIVER - RIVER USES Throughout the course of time, the Housatonic River has played a prominent role in the growth and development of the valley land which surrounds it. The earliest settlers, the Mohican Indians, migrated out of New York's Hudson Valley, coming over the Taconic Mountains. Arriving in Massachusetts more than 10,000 years ago, the Indians settled along the river's banks, farmed the river's nutrient-rich floodplains and fished the river for food. The first English colonists arrived in 1639, settling in Stratford at the mouth of the river. Agriculture was the major activity throughout the valley for much of the next century, and is still evident today where the Housatonic meanders through southern Massachusetts, and into Kent and New Milford in Connecticut, creating wide, fertile floodplains. The river was mainly used by the early colonists for transportation and waste disposal. Farther south, Derby was a shipping and fishing port, where shipbuilding flourished for almost 200 years. During the 18th and 19th century, water power played a dominant role in the development of industry throughout the valley, and remnants of dams, mill races and furnaces can still be seen today. In the northwest hills of Connecticut high quality iron ore was abundant. The ore was melted with limestone in blast furnaces, molded into finished iron utensils, tools and armaments and then cooled with river water. Many forests were cleared to make the charcoal used as fuel in the furnaces. The iron industry began in Salisbury in 1730, and more than 40 blast furnaces were in operation from Lanesboro to Kent during the 1800's. One of the best known examples is the Kent Furnace, built in 1864. The last furnace ceased operation in 1923. The 1800's brought a shift to manufacturing and extensive mining of marble and limestone in the "Marble Valley" of northwestern Connecticut, and the start of paper making. The Pittsfield region was the first area in the nation to start making paper, and by the end of the Civil War there were at least 28 paper mills in Berkshire County alone! About this same time, tobacco farming began in the Still River valley, reaching its peak near the end of the century. By 1850, most towns up and down the river had small factories along the Housatonic's banks, using the river as both a source of water for their manufacturing or milling processes and a dumping ground for their waste products. The mills and factories eventually polluted the river, and it wasn't until the passage of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments (1972) and the Clean Water Act (1977) that a system was created for reducing and controlling pollutant loading into the river, by mandating treatment for the removal of chemicals from wastewater discharges. Since the earliest colonial times, the river has been used as a source of power. The earliest dams were built to operate gristmills and sawmills, and later to turn turbines. In 1870 the first dam was constructed across the river between Derby and Shelton for the generation of electric power. Other hydroelectric power dams were built in Great Barrington, Falls Village (1914), Kent (Bulls Bridge, 1902), New Milford (Rocky River, (1928), Monroe (Stevenson, 1919) and Southbury (Shepaug, 1955). Hydroelectric power generation remains an important river use today. The onset of the 20th century brought with it the decline of industrialization in the valley. While no one knows for sure, it is believed that the decline was caused by inadequate roadway transportation routes and railroad systems along with competition from larger industries located outside of the Housatonic River valley. Industry survived only in the areas of Pittsfield, Danbury, and from the Naugatuck valley to the mouth of the river. Throughout time, the Housatonic River has provided bountiful recreational opportunities. There are more than 100,000 acres of public recreation land in the watershed, offering hunting, hiking, camping, winter sports and water-based activities. The waters of the Housatonic River provide excellent white-water canoeing, kayaking, tubing, boating and swimming. For the expert, Rattlesnake Rapids in Falls Village and Bull's Bridge in Kent offer challenging white-water runs. Flat water canoeing is at its best in the gentler currents found through southern Massachusetts, West Cornwall and Kent as the river flows past meadows and picturesque farms. Hikers will enjoy a splendid view of the river from the Appalachian Trail where it parallels the river as it passes through Sharon, Cornwall and Kent. Fishing is a major activity along the entire length of the river and its tributaries. Trout, bass, and perch abound and some of the best fly fishing can be found in northwestern Connecticut. Farther south, Candlewood Lake and the Housatonic's three instream lakes, Lillinonah, Zoar and Housatonic provide opportunities for motor boating, fishing, water-skiing and swimming. Near the Shepaug Dam, one can view the endangered bald eagle, nesting and feeding near the river during the winter months. The tidal Housatonic estuary provides coastal recreation, commercial fishing and critical habitats for rare plants and animals. The estuary is also a significant contributor to the state's shellfish population, is the most consistent producer of seed oysters in the northeast as a public oyster bed and generates over one-third of all oyster seed available to the state shellfish industry. The role of the Housatonic River in our future lives will depend on how well we learn to balance the many competing, and often conflicting, demands that we make on the river and its surrounding lands. Housatonic River Estuary . . . its wildlife, history, activities, water quality

What is an estuary?

The Housatonic River begins its 149-mile journey to Long Island Sound in Massachusetts. It flows south through western Massachusetts and Connecticut becoming tidal just below the Derby/Shelton Dam, and becomes an estuary at approximately the Far Mill River in southern Connecticut. The Housatonic River estuary is made up of different landforms, or habitats, each having its own community of plants and animals which have adapted to local conditions and are dependent upon one another. All living things within a habitat are tied together by a food web. Plants and algae are producers, using sunlight and nutrients to make food energy. The plants and algae are then consumed by microscopic animals, shellfish, larger fish, insects, turtles, rodents, and deer. Larger hunters, including hawks, bats, skunks, and raccoons consume insects or small land animals. Large fish and water birds such as the herons, terns, egrets, and osprey consume smaller fish. Nutrients are returned to the natural community through the bacteria and fungi which decompose dead plants and animals. Every species in the food web eats, or is eaten by, another species. Although estuaries, by their very nature, are resilient to change and environmental upset, human activities, if severe enough, can disrupt the food web. The disruption of even one species in this web causes a change in the entire network. Overfishing, pollution, and habitat destruction have caused species to disappear from the Housatonic estuary. Estuary Habitats The Housatonic estuary includes four types of habitat: uplands (well-drained soils with elevations up to 500 feet), tidal wetlands and mud flats, sand spits and barrier beaches, and Long Island Sound. The tidal wetlands and mud flats, low-lying areas that flood at high tide and are exposed at low tide, are one of the most important habitats in the estuary. Marsh plants slow and soak up flood waters, filter out chemicals and partially break down and take in pollutants, and also prevent land erosion by absorbing the force of wind and waves. Microscopic organisms and bacteria in tidal marshes break down dead plant and animal matter, cleaning the water and recycling nutrients into the estuary. Since the late 1800s, 29 percent of Connecticut's tidal wetlands have been lost due to construction, dredging, draining, dumping, and pollution. The Tidal Wetlands Act of 1969 has helped to save the remaining marshlands, with an average annual loss of wetlands since then estimated at one-quarter acre per year. Milford Point at the river's mouth, and Long Beach, west of Stratford Point, are sand spits and barrier beaches, which are important breeding areas for coastal birds and provide habitat for migrant and wintering species. A Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection program protects critical nesting sites of threatened species on Milford Point and the Great Meadows Salt Marsh in Stratford. Fencing the nesting areas and public education have helped increase nesting pairs in the estuary. Threatened estuary wildlife species include the piping plover, least tern and the horned lark. Threatened plants are panic grass, beach needlegrass and false beach heather. The grasshopper sparrow is an endangered bird and endangered plants include the coast violet, lizard's tail and saltpond grass. In Long Island Sound and at the mouth of the Housatonic River, plants and animals living in the open water are either bottom-dwelling, called benthos, or dwell in the water column, which supports a wide variety of life including anadromous fish, such as Atlantic salmon. Anadromous fish must migrate into fresh water to lay eggs, or spawn. After the young hatch, they swim to salt water to mature. Anadromous populations have declined because dams on the Housatonic River prevent the fish from reaching their spawning grounds. Estuary Facts

Housatonic River & Estuary

Long Island Sound

1,300 square miles, 110 miles long, and 21 miles wide at its widest point.

577 miles of coastline, 95 miles of public beaches.

History of the estuary The original settlers in the Housatonic River valley were the Paugussett Indians, part of the Algonquian nation, who migrated from New York. They named the upper part of the river Pootatuck, or River of the Great Falls. Eventually, the Indian name Ousatonic, meaning place beyond the mountains, was given to the Housatonic River. The tribes settled along the riverbanks, farmed the fertile floodplains and harvested finfish and shellfish. Inland groups of Indians also traveled to Long Island Sound for salt and fish. The first record of the Housatonic made by a European was in 1614 by Dutch explorer Adrian Block, who sailed eastward from the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam (New York). He named the river the River of Roodenberg, or River of the Red Hills. The west shore of the lower Housatonic River valley was later settled by English colonists in 1639, when Reverend Adam Blakeman and many families from his church left Wethersfield, Connecticut and followed Indian trails to the river shoreline. They chose a protected harbour the Indians called Cupheag (The harbour), where they began the town of Stratford. An historic marker, located on Shore Road behind the American Shakespeare Theatre, marks the location of Cupheag, now called Mac's harbour. In the same year a group of English colonists from the Quinnipiac (New Haven) colony bought land surrounding the Wepawaug River from the Paugussett Indians and founded the Wepawaug Colony, which became Milford. Wepawaug colonists used Milford Point and the marshy eastern shore of the Housatonic for fishing, digging oysters, and hunting. From these two settlements the English colonists moved up the river valley, driving out most of the Indians, until they settled the entire valley. The settlers depended on the river to survive and to move goods and people (the steep hills rising from the river shore made road building difficult). Each year spring floods deposited a new layer of fertile soil onto the flood plains. The colonists grew Indian corn, oats, barley, peas, beans, turnip, squash, and pumpkins and harvested spartina, one of the salt marsh grasses, to feed their farm animals. The river also provided an abundant supply of fish, clams, and oysters, and many migratory birds. As the settlements grew, colonists harvested lumber, crops, and fish to trade with England and the English Caribbean colonies. The towns of Stratford, Huntington (Shelton), and Derby became commercial hubs where timber, fish, livestock, and crops were marketed to Boston, New York, Europe, and the West Indies. Shipbuilding The shipbuilding industry flourished in the Housatonic River estuary from the mid-1600s through the 1800s. One of the earliest shipyards was built in 1657 by Thomas Wheeler at Derby Landing just below the confluence of the Housatonic and Naugatuck Rivers. Hallock's shipyard, the largest in the valley, launched 52 ships between 1824-1868. In 1685, across the river in Ripton (Shelton), Dr. Thomas Leavenworth built a warehouse, tannery and shipyard that operated from 1760 to 1812, and launched ocean-going schooners, sloops, and brigs. This land is now the site of Indian Well State Park. James Bennett's shipyard in Stratford, built in 1696, is now the Sikorsky Aircraft complex. In the early 1700s, Daniel Curtis opened a shipyard at the mouth of Ferry Creek and large schooners were built there during the mid-1800s. The 280-ton Helen Mar was launched in 1855, and the last boat was built there in 1938. This site is now the Stratford Marina. The last large shipyard was Housatonic Shipbuilding, where in 1918 the 2,551-ton, 267-foot steamship Fairfield was launched. The Housatonic estuary communities remained major seaports until improved roads and railroads provided land access to markets and transportation centers. Completion of the Ousatonic Dam in Shelton and Derby in 1870 changed the river flow causing silt to build up below the dam making the river too shallow for large, ocean-going ships. Bridges Washington Bridge, fifth bridge on its site since 1802, was built in 1921 and carries U.S. 1 across the river. The I-95 bridge is named for the first ferryman, Moses Wheeler. The railroad bridge is on the national register, fourth bridge at its location; the first, built in 1848, was, at 1,293 feet, the longest covered bridge ever built in Connecticut. The Merritt Parkway bridge, named for aviation pioneer Igor Sikorsky, is due for replacement in 1997. Manufacturing Housatonic colonists built lumber mills for house construction and grist mills for flour. Paper, woolen, and bark mills followed. Mac's harbour is believed to be the site of the first mill in the river valley, most likely a grain mill powered by the Housatonic River tides. James Blakeman built the first mill on the Far Mill River, between Stratford and Shelton, in 1676. By the Revolutionary War, the Far Mill River supported 11 mills from source to mouth. Blakeman also built a dam on the Near Mill River in Stratford in 1685, which powered mills until the 1770s. The dam and pond, known as Peck's Mill Pond, now forms a town park. Small mills and foundries serving local needs were built in the Housatonic valley until the mid-1800s. In 1833, Sheldon Smith, his brother, Fitch, John Lewis and Anson G. Phelps, built the Birmingham Canal System on the Naugatuck River just above its confluence with the Housatonic. The village of Birmingham, which grew around the dam and canal to form the downtown business district of Derby. The first factory along the canal, The Birmingham Iron Foundry, was completed in 1836, the same year that Edward N. Shelton and his brother-in-law, Nathan C. Sanford, built the Shelton Tack Company. By 1847, the village of Birmingham had 13 factories, using 18 water wheels. Edward Shelton formed the Ousatonic Water Company in 1866 and completed the Ousatonic Dam spanning the river between Derby and Shelton in 1870, creating the first hydropower impoundment on the Housatonic River. The dam and canal attracted manufacturers to the west shore of the river in the Town of Huntington. By 1880, 12 factories, employing 1,000, were on the canal; eight still stand. In 1882, Huntington Landing became the borough of Shelton, named for Edward N. Shelton. By the early 1900s a mile of factories lined the Shelton river shoreline, and today, in Shelton and Derby, industrial development continues with new, state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities.Ê Fishing Since the earliest days of English settlement, the Housatonic River has supported commercial fishing. The most important commercial fish taken from the Housatonic River was the American shad. The adult males weigh up to six pounds and females as much as 12 pounds. Shad feed at sea as adults, returning to fresh water to spawn. By the mid-1800s shad fishing was an important seasonal occupation, which ended with the construction of the Housatonic Dam in 1870. For 20 years after that, shad could not pass the dam into the upper Housatonic to spawn and were easily caught. By the end of the 1800s the species had disappeared from the Housatonic. Harvesting of American oysters from the floor of the Sound and the Housatonic estuary between Milford and Stratford began in the mid-1700s. During the 19th century the oystermen in Stratford and Milford discovered that the free swimming oyster larvae, called spat, attach to empty oyster shells about two weeks after birth, where they grow for the rest of their lives. Spreading oyster shells onto the oyster beds in July would encourage spat growth. The oystermen's demand for shells encouraged a unique operation known as shelling in Stratford. The shellermen would tong shells or run a powerboat over the beds to "kick" the shells loose so they could be scooped or tonged. Nell's Island was a favorite spot to store shells for sale. Until the mid-1970s, pollution, over-fishing, predators, and hurricane damage caused the decline of oyster harvesting. The Connecticut oyster industry has been rebuilt through pollution control, erosion reduction to keep mud from covering spat, and good aquaculture practices. Now two-year-old seed oysters grown in the Housatonic estuary are transplanted offshore in Long Island Sound to grow in cleaner water for two or three years before they are harvested. The oyster beds are protected by the Connecticut Department of Agriculture and the Stratford Shellfish Commission. Connecticut has the largest aquaculture industry in New England. The Housatonic oyster beds are Connecticut's major producers of seed oysters, and one of the largest north of Chesapeake Bay. Many oyster beds in Long Island Sound are also cultivated for hard-shell clams, which is second only to the oyster as a commercially harvested shellfish. The beds are dredged to harvest clams after the seed oysters are removed. The hard-shell clam, also known as the quahog, littleneck, or cherrystone clam, was gathered by the coastal Indians for food. The shells were used as containers and tools, and were made into wampum beads for money and ceremonial use.

Ducks and the Decoy Carvers In the estuary, huge flocks of migratory water birds once blotted out the sun. In the 19th century, market hunters could bag two dozen birds with a single shot and ship them to New York. In 1863, a gentleman duck hunter named Albert Laing came to Stratford to live. He carved realistic decoys, high-chested to battle river currents, and began the Stratford school of decoy carving. Others emulated Laing, the most noted being Charles E. Shang Wheeler, oysterman, state senator, and naturalist. Shang's decoys and Laing's both sell for $60,000 or more today. Watersheds and water quality All rivers flow toward the sea, propelled by the force of gravity. The 1,948-square-mile Housatonic River watershed collects rain, snow and sheds it into the groundwater, streams and rivers which flow into the Housatonic River. A drop of water falling anywhere in this watershed eventually arrives at Long Island Sound along with contaminants (nonpoint source pollution) such as oil, gasoline, fertilizers, pesticides, and road salt picked up along its journey from buildings, roads, parking lots, lawns and gardens. Joined by point source discharges from pipes at industrial facilities and wastewater treatment plants, pollution draining from anywhere in the watershed may affect water quality in the estuary and Sound, and, if severe enough, harm plant and animal life and disrupt the food web. Water quality in the estuary There was a time when estuary shellfish were tinted blue-green, the result of high copper levels in discharges from metal finishing plants on the Naugatuck River which flows into the Housatonic at Derby. Copper, chromium and lead were introduced into the Naugatuck and Housatonic rivers through industrial and wastewater treatment plant discharges and combined sewer overflows. The regulation of point source discharges, upgrading of municipal wastewater treatment plants and elimination of most combined sewer overflows significantly decreased the concentrations of most heavy metals in the Housatonic River and estuary. Several million pounds of lead pellets lie in the sediments at the mouth of the Housatonic at Stratford's Lordship Point, the legacy of past trap and skeet shooting. This lead threatens waterfowl and aquatic life. It is estimated that half of the wintering black ducks that feed in the shallow waters on mussels, snails, sea worms and seeds have been poisoned by the lead. Fortunately, cleanup plans include site dredging, recovering lead from the dredged sediment and returning clean sediment to the site. Saltwater, tidal and water circulation patterns have been affected by historic unregulated sand and gravel mining activities in the estuary which left behind deep dredge holes. Fine grain materials and organics settled in these pits, using up oxygen, leaving behind aquatic deserts where life cannot exist. Today, dredging is regulated and generally confined to navigational channels. Floatable debris (flotsam), such as plastic utensils and wrappers, paper cups, bottles, cigarettes, cans and other litter enter streams and rivers where they often injure or kill turtles, fish, birds and other life by direct ingestion or entanglement. Today's major water quality problem in the estuary is nutrient loading. Nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon enter the Housatonic River and its tributaries from wastewater treatment plant discharges. However, this source continues to decline --- the result of ongoing state efforts to upgrade plants to require advanced treatment. A continuing source of nutrient loading is nonpoint source pollution. Atmospheric deposition of airborne pollutants and runoff from urban and suburban areas, septic systems, lawns, gardens, roadways, construction sites and upstream agricultural activities carry nutrients into storm drains, brooks, streams and eventually into the Housatonic River. Because these are widespread, they are difficult to identify and costly to regulate, and remain a contributor of nitrogen to Long Island Sound, which affects the Sound's major water quality problem, hypoxia. Hypoxia In recent years a condition known as hypoxia, low dissolved oxygen levels in the water, has been developing in Long Island Sound. In summer, the sun heats the water near the surface and the dense, cooler water lies in a layer along the bottom. These two layers do not mix. Decomposing organisms in the bottom layer use up dissolved oxygen, and when the water of the estuary is calm there are no waves to mix in more oxygen. At least three parts per million of dissolved oxygen in the water is needed to protect most estuarine species. If the oxygen level falls below this level, hypoxia occurs, and some bottom-dwellers may be affected. The condition gets worse excess nutrients flow into the Sound. The nutrients cause algae to "bloom" or grow explosively. When these algae die, they sink to the bottom increasing decomposition, sometimes using up almost all the dissolved oxygen thereby threatening all marine life. Vision for the Future Open space along the Housatonic riverfront is vital in maintaining the health, beauty, and natural diversity of the river's ecosystem, but intensive development is eliminating it. Comprehensive land protection and management plans can preserve open space by balancing conservation with orderly growth. To achieve this, HVA has initiated the Housatonic RiverBelt Greenway project which brings together community groups and local governments to create a "greenway" of parks, river access points, and protected lands linked by walking and biking paths from Long Island Sound to the river's source in Massachusetts. Stops along the way tourism is a vital and growing part of the economy in the lower Housatonic River valley. The area's natural beauty and location on the river and Long Island Sound attract many visitors each year. Recreational fishing alone draws thousands of visitors to the Housatonic estuary. The most popular game fish are bluefish, blackfish (tautog), striped bass, summer flounder (fluke), and winter flounder. Sport fishing also generates business for local marinas, bait and tackle shops, outfitters, and restaurants. |